for what is achilles willing to fight and for what does he refuse to fight?

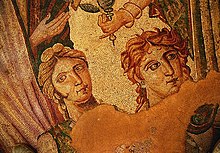

Aboriginal Greek polychromatic pottery painting (dating to c. 300 BC) of Achilles during the Trojan State of war

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ə-KIL-eez) or Achilleus (Greek: Ἀχιλλεύς ) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and is the key character of Homer's Iliad. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, male monarch of Phthia.

Achilles' most notable feat during the Trojan War was the slaying of the Trojan prince Hector outside the gates of Troy. Although the decease of Achilles is not presented in the Iliad, other sources hold that he was killed near the end of the Trojan War by Paris, who shot him with an arrow. Later legends (beginning with Statius' unfinished epic Achilleid, written in the 1st century AD) land that Achilles was invulnerable in all of his torso except for 1 heel, because when his mother Thetis dipped him in the river Styx as an infant, she held him past ane of his heels. Alluding to these legends, the term "Achilles' heel" has come to mean a betoken of weakness, especially in someone or something with an otherwise strong constitution. The Achilles tendon is besides named later him due to these legends.

Etymology

Linear B tablets attest to the personal name Achilleus in the forms a-ki-re-u and a-ki-re-nosotros,[ane] the latter beingness the dative of the old.[2] The proper noun grew more popular, even becoming common before long after the 7th century BC[iii] and was also turned into the female form Ἀχιλλεία (Achilleía), attested in Attica in the 4th century BC (IG II² 1617) and, in the form Achillia, on a stele in Halicarnassus as the proper noun of a female gladiator fighting an "Amazon".

Achilles' proper noun can be analyzed as a combination of ἄχος ( áchos ) "distress, pain, sorrow, grief"[4] and λαός ( laós ) "people, soldiers, nation", resulting in a proto-class *Akhí-lāu̯os "he who has the people distressed" or "he whose people accept distress".[5] [6] The grief or distress of the people is a theme raised numerous times in the Iliad (and often by Achilles himself). Achilles' role as the hero of grief or distress forms an ironic juxtaposition with the conventional view of him as the hero of κλέος kléos ("glory", usually in war). Furthermore, laós has been construed by Gregory Nagy, following Leonard Palmer, to mean "a corps of soldiers", a muster.[6] With this derivation, the name obtains a double pregnant in the poem: when the hero is functioning rightly, his men bring distress to the enemy, but when wrongly, his men go the grief of state of war. The poem is in part about the misdirection of anger on the part of leadership.

Another etymology relates the proper name to a Proto-Indo-European chemical compound *h₂eḱ-pṓds "sharp human foot" which offset gave an Illyrian *āk̂pediós, evolving through time into *ākhpdeós and and so *akhiddeús. The shift from -dd- to -ll- is and so ascribed to the passing of the name into Greek via a Pre-Greek source. The first root part *h₂eḱ- "sharp, pointed" as well gave Greek ἀκή (akḗ "indicate, silence, healing"), ἀκμή (akmḗ "signal, edge, zenith") and ὀξύς (oxús "sharp, pointed, smashing, quick, clever"), whereas ἄχος stems from the root *h₂egʰ- "to be upset, afraid". The whole expression would be comparable to the Latin acupedius "swift of foot". Compare also the Latin word family unit of aciēs "sharp edge or point, battle line, battle, engagement", acus "needle, pin, bodkin", and acuō "to make pointed, sharpen, whet; to exercise; to agitate" (whence acute).[seven] Some topical epitheta of Achilles in the Iliad betoken to this "swift-footedness", namely ποδάρκης δῖος Ἀχιλλεὺς (podárkēs dĩos Achilleús "swift-footed divine Achilles")[viii] or, even more frequently, πόδας ὠκὺς Ἀχιλλεύς (pódas ōkús Achilleús "quick-footed Achilles").[9]

Some researchers deem the name a loan word, possibly from a Pre-Greek language.[ane] Achilles' descent from the Nereid Thetis and a similarity of his name with those of river deities such equally Acheron and Achelous have led to speculations about his being an old water divinity (meet beneath Worship).[ten] Robert South. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin of the name, based among other things on the coexistence of -λλ- and -λ- in ballsy linguistic communication, which may account for a palatalized phoneme /ly/ in the original language.[2]

Nascence and early on years

Achilles was the son of the Thetis, a nereid, and Peleus, the king of the Myrmidons. Zeus and Poseidon had been rivals for Thetis'south hand in marriage until Prometheus, the fore-thinker, warned Zeus of a prophecy (originally uttered past Themis, goddess of divine police force) that Thetis would behave a son greater than his father. For this reason, the two gods withdrew their pursuit, and had her wed Peleus.[eleven]

In that location is a tale which offers an alternative version of these events: In the Argonautica (4.760) Zeus' sister and wife Hera alludes to Thetis' chaste resistance to the advances of Zeus, pointing out that Thetis was so loyal to Hera's wedlock bond that she coolly rejected the father of gods. Thetis, although a daughter of the bounding main-god Nereus, was likewise brought upwards by Hera, further explaining her resistance to the advances of Zeus. Zeus was furious and decreed that she would never marry an immortal.[12]

According to the Achilleid, written by Statius in the 1st century Advertisement, and to not-surviving previous sources, when Achilles was born Thetis tried to make him immortal by dipping him in the river Styx; however, he was left vulnerable at the part of the body by which she held him: his left heel[13] [14] (see Achilles' heel, Achilles' tendon). It is not clear if this version of events was known earlier. In another version of this story, Thetis all-powerful the male child in ambrosia and put him on peak of a fire in order to burn abroad the mortal parts of his torso. She was interrupted past Peleus and abandoned both father and son in a rage.[15]

None of the sources before Statius make any reference to this full general invulnerability. To the contrary, in the Iliad, Homer mentions Achilles being wounded: in Book 21 the Paeonian hero Asteropaeus, son of Pelagon, challenged Achilles by the river Scamander. He was ambidextrous, and bandage a spear from each hand; ane grazed Achilles' elbow, "drawing a spurt of blood".[16]

In the few bitty poems of the Epic Cycle which draw the hero's death (i.e. the Cypria, the Petty Iliad past Lesches of Pyrrha, the Aithiopis and Iliou persis by Arctinus of Miletus), there is no trace of whatsoever reference to his general invulnerability or his famous weakness at the heel. In the later vase paintings presenting the death of Achilles, the arrow (or in many cases, arrows) hit his torso.

Peleus entrusted Achilles to Chiron the Centaur, who lived on Mountain Pelion, to be reared.[17] Thetis foretold that her son's fate was either to proceeds glory and die young, or to live a long only uneventful life in obscurity. Achilles chose the sometime, and decided to take function in the Trojan State of war.[eighteen] According to Homer, Achilles grew upwards in Phthia with his companion Patroclus.[one]

Co-ordinate to Photius, the sixth book of the New History by Ptolemy Hephaestion reported that Thetis burned in a hugger-mugger identify the children she had past Peleus. When she had Achilles, Peleus noticed, tore him from the flames with just a burnt human foot, and confided him to the centaur Chiron. Afterward Chiron exhumed the body of the Damysus, who was the fastest of all the giants, removed the ankle, and incorporated it into Achilles' burnt foot.[19]

Other names

Among the appellations under which Achilles is generally known are the following:[20]

- Pyrisous, "saved from the burn", his first name, which seems to favour the tradition in which his mortal parts were burned by his mother Thetis

- Aeacides, from his grandfather Aeacus

- Aemonius, from Aemonia, a country which afterwards acquired the name of Thessaly

- Aspetos, "inimitable" or "vast", his name at Epirus

- Larissaeus, from Larissa (also called Cremaste), a town of Thessaly, which still bears the same name

- Ligyron, his original name

- Nereius, from his mother Thetis, i of the Nereids

- Pelides, from his father, Peleus

- Phthius, from his birthplace, Phthia

- Podarkes, "swift-footed", due to the wings of Arke being attached to his feet.[21]

Subconscious on Skyros

Some post-Homeric sources[22] claim that in order to go on Achilles safe from the war, Thetis (or, in some versions, Peleus) hid the young man at the court of Lycomedes, rex of Skyros.

There, Achilles was bearded equally a girl and lived among Lycomedes' daughters, perhaps nether the name "Pyrrha" (the ruddy-haired girl), Cercysera or Aissa ("swift"[23]).[24] With Lycomedes' daughter Deidamia, whom in the account of Statius he raped, Achilles at that place fathered ii sons, Neoptolemus (also called Pyrrhus, after his father's possible alias) and Oneiros. According to this story, Odysseus learned from the prophet Calchas that the Achaeans would exist unable to capture Troy without Achilles' aid. Odysseus went to Skyros in the guise of a peddler selling women'south clothes and jewellery and placed a shield and spear amid his appurtenances. When Achilles instantly took up the spear, Odysseus saw through his disguise and convinced him to join the Greek entrada. In another version of the story, Odysseus bundled for a trumpet alarm to be sounded while he was with Lycomedes' women. While the women fled in panic, Achilles prepared to defend the court, thus giving his identity abroad.

In the Trojan War

According to the Iliad, Achilles arrived at Troy with 50 ships, each carrying fifty Myrmidons. He appointed five leaders (each leader commanding 500 Myrmidons): Menesthius, Eudorus, Peisander, Phoenix and Alcimedon.[25]

Telephus

When the Greeks left for the Trojan War, they accidentally stopped in Mysia, ruled past Male monarch Telephus. In the resulting battle, Achilles gave Telephus a wound that would not heal; Telephus consulted an oracle, who stated that "he that wounded shall heal". Guided past the oracle, he arrived at Argos, where Achilles healed him in club that he might go their guide for the voyage to Troy.[26]

According to other reports in Euripides' lost play about Telephus, he went to Aulis pretending to be a beggar and asked Achilles to heal his wound. Achilles refused, claiming to have no medical knowledge. Alternatively, Telephus held Orestes for ransom, the ransom being Achilles' aid in healing the wound. Odysseus reasoned that the spear had inflicted the wound; therefore, the spear must exist able to heal it. Pieces of the spear were scraped off onto the wound and Telephus was healed.[26]

Troilus

Achilles slaying Troilus, crimson-effigy kylix signed past Euphronios

According to the Cypria (the function of the Epic Bike that tells the events of the Trojan State of war earlier Achilles' wrath), when the Achaeans desired to return home, they were restrained by Achilles, who afterwards attacked the cattle of Aeneas, sacked neighbouring cities (like Pedasus and Lyrnessus, where the Greeks capture the queen Briseis) and killed Tenes, a son of Apollo, besides as Priam's son Troilus in the sanctuary of Apollo Thymbraios; all the same, the romance betwixt Troilus and Chryseis described in Geoffrey Chaucer'south Troilus and Criseyde and in William Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida is a medieval invention.[27] [1]

In Dares Phrygius' Account of the Devastation of Troy,[28] the Latin summary through which the story of Achilles was transmitted to medieval Europe, also equally in older accounts, Troilus was a young Trojan prince, the youngest of King Priam's and Hecuba'south five legitimate sons (or according other sources, another son of Apollo).[29] Despite his youth, he was one of the chief Trojan war leaders, a "horse fighter" or "chariot fighter" according to Homer.[30] Prophecies linked Troilus' fate to that of Troy and so he was ambushed in an endeavour to capture him. Even so Achilles, struck by the beauty of both Troilus and his sister Polyxena, and overcome with lust, directed his sexual attentions on the youth – who, refusing to yield, instead found himself decapitated upon an altar-omphalos of Apollo Thymbraios.[31] [32] Later versions of the story suggested Troilus was accidentally killed past Achilles in an over-agog lovers' embrace.[33] In this version of the myth, Achilles' death therefore came in retribution for this sacrilege.[31] [34] Aboriginal writers treated Troilus equally the prototype of a dead kid mourned by his parents. Had Troilus lived to adulthood, the First Vatican Mythographer claimed, Troy would have been invincible; even so, the motif is older and institute already in Plautus' Bacchides.[35]

In the Iliad

Homer's Iliad is the almost famous narrative of Achilles' deeds in the Trojan War. Achilles' wrath (μῆνις Ἀχιλλέως, mênis Achilléōs) is the key theme of the poem. The first two lines of the Iliad read:

| Μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληιάδεω Ἀχιλῆος οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί' Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε' ἔθηκε, [...] | Sing, Goddess, of the rage of Peleus' son Achilles, the accursed rage that brought swell suffering to the Achaeans, [...] |

The Homeric epic merely covers a few weeks of the decade-long war, and does not narrate Achilles' death. It begins with Achilles' withdrawal from boxing afterward being dishonoured by Agamemnon, the commander of the Achaean forces. Agamemnon has taken a adult female named Chryseis as his slave. Her father Chryses, a priest of Apollo, begs Agamemnon to return her to him. Agamemnon refuses, and Apollo sends a plague amongst the Greeks. The prophet Calchas correctly determines the source of the troubles but will not speak unless Achilles vows to protect him. Achilles does so, and Calchas declares that Chryseis must be returned to her father. Agamemnon consents, merely then commands that Achilles' battle prize Briseis, the girl of Briseus, be brought to him to supercede Chryseis. Angry at the dishonour of having his plunder and glory taken away (and, equally he says later, because he loves Briseis),[36] with the urging of his mother Thetis, Achilles refuses to fight or lead his troops alongside the other Greek forces. At the same fourth dimension, burning with rage over Agamemnon'southward theft, Achilles prays to Thetis to convince Zeus to help the Trojans gain footing in the war, and then that he may regain his honour.

As the battle turns against the Greeks, thanks to the influence of Zeus, Nestor declares that the Trojans are winning because Agamemnon has angered Achilles, and urges the male monarch to appease the warrior. Agamemnon agrees and sends Odysseus and two other chieftains, Ajax and Phoenix. They promise that, if Achilles returns to battle, Agamemnon will return the convict Briseis and other gifts. Achilles rejects all Agamemnon offers him and simply urges the Greeks to sail abode every bit he was planning to do.

The Trojans, led by Hector, subsequently push the Greek regular army back toward the beaches and assail the Greek ships. With the Greek forces on the verge of absolute destruction, Patroclus leads the Myrmidons into battle, wearing Achilles' armour, though Achilles remains at his camp. Patroclus succeeds in pushing the Trojans back from the beaches, simply is killed by Hector earlier he tin atomic number 82 a proper set on on the city of Troy.

After receiving the news of the death of Patroclus from Antilochus, the son of Nestor, Achilles grieves over his beloved companion'due south expiry. His mother Thetis comes to comfort the distraught Achilles. She persuades Hephaestus to make new armour for him, in place of the armour that Patroclus had been wearing, which was taken past Hector. The new armour includes the Shield of Achilles, described in keen detail in the poem.

Enraged over the death of Patroclus, Achilles ends his refusal to fight and takes the field, killing many men in his rage but always seeking out Hector. Achilles even engages in boxing with the river god Scamander, who has become aroused that Achilles is choking his waters with all the men he has killed. The god tries to drown Achilles just is stopped past Hera and Hephaestus. Zeus himself takes note of Achilles' rage and sends the gods to restrain him so that he will not get on to sack Troy itself earlier the fourth dimension allotted for its destruction, seeming to testify that the unhindered rage of Achilles tin defy fate itself. Finally, Achilles finds his prey. Achilles chases Hector around the wall of Troy three times before Athena, in the form of Hector's favorite and dearest brother, Deiphobus, persuades Hector to stop running and fight Achilles face to face up. Afterward Hector realizes the play a trick on, he knows the battle is inevitable. Wanting to go downwards fighting, he charges at Achilles with his but weapon, his sword, but misses. Accepting his fate, Hector begs Achilles not to spare his life, but to treat his body with respect afterward killing him. Achilles tells Hector information technology is hopeless to expect that of him, declaring that "my rage, my fury would drive me now to hack your flesh away and eat you raw – such agonies yous accept caused me".[37] Achilles then kills Hector and drags his corpse past its heels behind his chariot. After having a dream where Patroclus begs Achilles to hold his funeral, Achilles hosts a series of funeral games in honour of his companion.[38]

At the onset of his duel with Hector, Achilles is referred to every bit the brightest star in the sky, which comes on in the autumn, Orion's domestic dog (Sirius); a sign of evil. During the cremation of Patroclus, he is compared to Hesperus, the evening/western star (Venus), while the burning of the funeral pyre lasts until Phosphorus, the morn/eastern star (too Venus) has set (descended).

With the assistance of the god Hermes (Argeiphontes), Hector's begetter Priam goes to Achilles' tent to plead with Achilles for the return of Hector's body then that he tin exist buried. Achilles relents and promises a truce for the elapsing of the funeral, lasting 9 days with a burial on the tenth (in the tradition of Niobe's offspring). The poem ends with a description of Hector's funeral, with the doom of Troy and Achilles himself still to come.

Later epic accounts: fighting Penthesilea and Memnon

Achilles and Memnon fighting, between Thetis and Eos, Cranium black-effigy amphora, c. 510 BC, from Vulci

The Aethiopis (7th century BC) and a work named Posthomerica, composed by Quintus of Smyrna in the fourth century CE, relate further events from the Trojan State of war. When Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons and daughter of Ares, arrives in Troy, Priam hopes that she volition defeat Achilles. After his temporary truce with Priam, Achilles fights and kills the warrior queen, simply to grieve over her death later.[39] At first, he was so distracted past her beauty, he did not fight as intensely as usual. One time he realized that his distraction was endangering his life, he refocused and killed her.

Post-obit the death of Patroclus, Nestor's son Antilochus becomes Achilles' closest companion. When Memnon, son of the Dawn Goddess Eos and rex of Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, slays Antilochus, Achilles in one case more than obtains revenge on the battleground, killing Memnon. Consequently, Eos will not let the sun ascension until Zeus persuades her. The fight between Achilles and Memnon over Antilochus echoes that of Achilles and Hector over Patroclus, except that Memnon (different Hector) was also the son of a goddess.

Many Homeric scholars argued that episode inspired many details in the Iliad 's description of the expiry of Patroclus and Achilles' reaction to it. The episode then formed the basis of the cyclic epic Aethiopis, which was composed after the Iliad, possibly in the 7th century BC. The Aethiopis is now lost, except for scattered fragments quoted by later authors.

Achilles tending Patroclus wounded by an arrow, Cranium reddish-figure kylix, c. 500 BC (Altes Museum, Berlin)

Achilles and Patroclus

The exact nature of Achilles' relationship with Patroclus has been a subject of dispute in both the classical period and modernistic times. In the Iliad, information technology appears to be the model of a deep and loyal friendship. Homer does not propose that Achilles and his close friend Patroclus had sexual relations.[twoscore] [41] Although there is no direct show in the text of the Iliad that Achilles and Patroclus were lovers, this theory was expressed past some later authors. Commentators from classical artifact to the present have often interpreted the relationship through the lens of their ain cultures. In 5th-century BCE Athens, the intense bond was frequently viewed in lite of the Greek custom of paiderasteia. In Plato'due south Symposium, the participants in a dialogue about love presume that Achilles and Patroclus were a couple; Phaedrus argues that Achilles was the younger and more cute ane so he was the beloved and Patroclus was the lover.[42] However, ancient Greek had no words to distinguish heterosexual and homosexual,[43] and it was causeless that a man could both want handsome young men and take sex with women. Many pairs of men throughout history have been compared to Achilles and Patroclus to imply a homosexual relationship.

Expiry

Dying Achilles (Achilleas thniskon) in the gardens of the Achilleion

The death of Achilles, fifty-fifty if considered solely as it occurred in the oldest sources, is a complex i, with many different versions.[44] In the oldest version, the Iliad, and equally predicted by Hector with his dying jiff, the hero's death was brought nearly by Paris with an arrow (to the heel co-ordinate to Statius). In some versions, the god Apollo guided Paris' pointer. Some retellings as well state that Achilles was scaling the gates of Troy and was hit with a poisoned arrow. All of these versions deny Paris whatsoever sort of valour, owing to the common conception that Paris was a coward and not the human being his brother Hector was, and Achilles remained undefeated on the battlefield.

After decease, Achilles' bones were mingled with those of Patroclus, and funeral games were held. He was represented in the Aethiopis as living after his death in the island of Leuke at the rima oris of the river Danube. Another version of Achilles' death is that he fell deeply in honey with one of the Trojan princesses, Polyxena. Achilles asks Priam for Polyxena'due south manus in marriage. Priam is willing considering it would hateful the cease of the state of war and an alliance with the world's greatest warrior. But while Priam is overseeing the individual spousal relationship of Polyxena and Achilles, Paris, who would have to give up Helen if Achilles married his sister, hides in the bushes and shoots Achilles with a divine arrow, killing him.

In the Odyssey, Agamemnon informs Achilles of his pompous burial and the erection of his mound at the Hellespont while they are receiving the expressionless suitors in Hades.[45] He claims they built a massive burial mound on the embankment of Ilion that could be seen by anyone approaching from the body of water.[46] Achilles was cremated and his ashes cached in the same urn as those of Patroclus.[47] Paris was later killed past Philoctetes using the enormous bow of Heracles.

In Volume xi of Homer's Odyssey, Odysseus sails to the underworld and converses with the shades. One of these is Achilles, who when greeted as "blessed in life, blessed in death", responds that he would rather be a slave to the worst of masters than be king of all the dead. Only Achilles and so asks Odysseus of his son's exploits in the Trojan war, and when Odysseus tells of Neoptolemus' heroic actions, Achilles is filled with satisfaction.[48] This leaves the reader with an cryptic understanding of how Achilles felt about the heroic life.

According to some accounts, he had married Medea in life, so that later on both their deaths they were united in the Elysian Fields of Hades – as Hera promised Thetis in Apollonius' Argonautica (3rd century BC).

Fate of Achilles' armour

Oinochoe, ca 520 BC, Ajax and Odysseus fighting over the armour of Achilles

Achilles' armour was the object of a feud between Odysseus and Telamonian Ajax (Ajax the greater). They competed for information technology by giving speeches on why they were the bravest after Achilles to their Trojan prisoners, who, later on considering both men'south presentations, decided Odysseus was more deserving of the armour. Furious, Ajax cursed Odysseus, which earned him the ire of Athena, who temporarily made Ajax so mad with grief and anguish that he began killing sheep, thinking them his comrades. After a while, when Athena lifted his madness and Ajax realized that he had actually been killing sheep, he was so ashamed that he committed suicide. Odysseus somewhen gave the armour to Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles. When Odysseus encounters the shade of Ajax much after in the House of Hades (Odyssey eleven.543–566), Ajax is nonetheless so aroused about the outcome of the competition that he refuses to speak to Odysseus.

A relic claimed to be Achilles' bronze-headed spear was preserved for centuries in the temple of Athena on the acropolis of Phaselis, Lycia, a port on the Pamphylian Gulf. The urban center was visited in 333 BCE by Alexander the Great, who envisioned himself as the new Achilles and carried the Iliad with him, merely his court biographers practice not mention the spear; withal, information technology was shown in the fourth dimension of Pausanias in the 2nd century CE.[49] [50]

Achilles, Ajax and a game of petteia

Numerous paintings on pottery have suggested a tale not mentioned in the literary traditions. At some betoken in the war, Achilles and Ajax were playing a lath game (petteia).[51] [52] They were absorbed in the game and oblivious to the surrounding battle.[53] The Trojans attacked and reached the heroes, who were saved only past an intervention of Athena.[54]

Worship and heroic cult

Detail of Achilles

The tomb of Achilles,[56] extant throughout artifact in Troad,[57] was venerated by Thessalians, but also past Persian expeditionary forces, as well equally by Alexander the Keen and the Roman emperor Caracalla.[58] Achilles' cult was likewise to exist found at other places, e. g. on the island of Astypalaea in the Sporades,[59] in Sparta which had a sanctuary,[60] in Elis and in Achilles' homeland Thessaly, equally well as in the Magna Graecia cities of Tarentum, Locri and Croton,[61] accounting for an almost Panhellenic cult to the hero.

The cult of Achilles is illustrated in the 500 BCE Polyxena sarcophagus, which depicts the sacrifice of Polyxena about the tumulus of Achilles.[62] Strabo (13.1.32) also suggested that such a cult of Achilles existed in Troad:[55] [63]

Near the Sigeium is a temple and monument of Achilles, and monuments also of Patroclus and Anthlochus. The Ilienses perform sacred ceremonies in honour of them all, and fifty-fifty of Ajax. Just they do not worship Hercules, alleging as a reason that he ravaged their country.

The spread and intensity of the hero'due south veneration amid the Greeks that had settled on the northern coast of the Pontus Euxinus, today's Black Sea, appears to have been remarkable. An archaic cult is attested for the Milesian colony of Olbia also as for an island in the middle of the Blackness Sea, today identified with Serpent Island (Ukrainian Зміїний, Zmiinyi, most Kiliya, Ukraine). Early on dedicatory inscriptions from the Greek colonies on the Black Bounding main (graffiti and inscribed clay disks, these possibly being votive offerings, from Olbia, the area of Berezan Island and the Tauric Chersonese[65]) attest the existence of a heroic cult of Achilles[66] from the sixth century BC onwards. The cult was still thriving in the tertiary century CE, when dedicatory stelae from Olbia refer to an Achilles Pontárchēs (Ποντάρχης, roughly "lord of the Body of water," or "of the Pontus Euxinus"), who was invoked as a protector of the city of Olbia, venerated on par with Olympian gods such every bit the local Apollo Prostates, Hermes Agoraeus,[58] or Poseidon.[67]

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) in his Natural History mentions a "port of the Achæi" and an "island of Achilles", famous for the tomb of that "human" ( portus Achaeorum, insula Achillis, tumulo eius viri clara ), situated somewhat nearby Olbia and the Dnieper-Problems Estuary; furthermore, at 125 Roman miles from this island, he places a peninsula "which stretches forth in the shape of a sword" obliquely, called Dromos Achilleos (Ἀχιλλέως δρόμος, Achilléōs drómos "the Race-grade of Achilles")[68] and considered the place of the hero's exercise or of games instituted past him.[58] This last feature of Pliny'south account is considered to be the iconic spit, called today Tendra (or Kosa Tendra and Kosa Djarilgatch), situated between the mouth of the Dnieper and Karkinit Bay, but which is inappreciably 125 Roman miles (c. 185 km) away from the Dnieper-Bug estuary, as Pliny states. (To the "Race-course" he gives a length of eighty miles, c. 120 km, whereas the spit measures c. seventy km today.)

In the following chapter of his volume, Pliny refers to the same island every bit Achillea and introduces two further names for it: Leuce or Macaron (from Greek [νῆσος] μακαρῶν "island of the blessed"). The "present day" measures, he gives at this betoken, seem to account for an identification of Achillea or Leuce with today'due south Serpent Isle.[69] Pliny's contemporary Pomponius Mela (c. 43 AD) tells that Achilles was cached on an isle named Achillea, situated betwixt the Borysthenes and the Ister, adding to the geographical confusion.[70] Ruins of a foursquare temple, measuring 30 meters to a side, possibly that dedicated to Achilles, were discovered by Captain Kritzikly (Russian: Критский, Николай Дмитриевич) in 1823 on Snake Island. A 2nd exploration in 1840 showed that the construction of a lighthouse had destroyed all traces of this temple. A 5th century BC black-glazed lekythos inscription, found on the isle in 1840, reads: "Glaukos, son of Poseidon, dedicated me to Achilles, lord of Leuke." In another inscription from the fifth or quaternary century BC, a statue is dedicated to Achilles, lord of Leuke, past a citizen of Olbia, while in a farther dedication, the city of Olbia confirms its continuous maintenance of the island's cult, once again suggesting its quality as a place of a supra-regional hero veneration.[58]

The heroic cult dedicated to Achilles on Leuce seems to go dorsum to an business relationship from the lost ballsy Aethiopis co-ordinate to which, subsequently his untimely decease, Thetis had snatched her son from the funeral pyre and removed him to a mythical Λεύκη Νῆσος (Leúkē Nêsos "White Island").[71] Already in the 5th century BC, Pindar had mentioned a cult of Achilles on a "vivid island" (φαεννά νᾶσος, phaenná nâsos) of the Black Sea,[72] while in another of his works, Pindar would retell the story of the immortalized Achilles living on a geographically indefinite Island of the Blest together with other heroes such equally his father Peleus and Cadmus.[73] Well known is the connectedness of these mythological Fortunate Isles (μακαρῶν νῆσοι, makárôn nêsoi) or the Homeric Elysium with the stream Oceanus which according to Greek mythology surrounds the inhabited world, which should have accounted for the identification of the northern strands of the Euxine with it.[58] Guy Hedreen has institute further prove for this connection of Achilles with the northern margin of the inhabited world in a poem by Alcaeus, speaking of "Achilles lord of Scythia"[74] and the opposition of Due north and South, equally evoked by Achilles' fight confronting the Aethiopian prince Memnon, who in his turn would be removed to his homeland past his female parent Eos subsequently his death.

The Periplus of the Euxine Sea (c. 130 AD) gives the following details:

It is said that the goddess Thetis raised this island from the sea, for her son Achilles, who dwells there. Hither is his temple and his statue, an primitive piece of work. This island is not inhabited, and goats graze on it, non many, which the people who happen to arrive hither with their ships, sacrifice to Achilles. In this temple are also deposited a great many holy gifts, craters, rings and precious stones, offered to Achilles in gratitude. 1 tin can nevertheless read inscriptions in Greek and Latin, in which Achilles is praised and celebrated. Some of these are worded in Patroclus' laurels, because those who wish to exist favored by Achilles, honour Patroclus at the same time. At that place are also in this island countless numbers of ocean birds, which look later on Achilles' temple. Every morning they wing out to ocean, wet their wings with h2o, and return chop-chop to the temple and sprinkle it. And later they finish the sprinkling, they clean the hearth of the temple with their wings. Other people say yet more, that some of the men who accomplish this isle, come here intentionally. They bring animals in their ships, destined to be sacrificed. Some of these animals they slaughter, others they set complimentary on the island, in Achilles' honour. But there are others, who are forced to come to this island by sea storms. Equally they have no sacrificial animals, but wish to become them from the god of the isle himself, they consult Achilles' oracle. They ask permission to slaughter the victims called from amidst the animals that graze freely on the island, and to deposit in exchange the price which they consider off-white. But in case the oracle denies them permission, because there is an oracle here, they add something to the price offered, and if the oracle refuses again, they add together something more, until at last, the oracle agrees that the toll is sufficient. And then the victim doesn't run away whatsoever more, but waits willingly to be caught. So, there is a great quantity of silver in that location, consecrated to the hero, as toll for the sacrificial victims. To some of the people who come to this isle, Achilles appears in dreams, to others he would appear even during their navigation, if they were not too far away, and would instruct them as to which function of the island they would amend anchor their ships.[75]

The Greek geographer Dionysius Periegetes, who probable lived during the first century CE, wrote that the island was called Leuce "because the wild animals which live there are white. It is said that in that location, in Leuce island, reside the souls of Achilles and other heroes, and that they wander through the uninhabited valleys of this island; this is how Jove rewarded the men who had distinguished themselves through their virtues, because through virtue they had acquired everlasting honour".[76] Similarly, others relate the island's proper name to its white cliffs, snakes or birds dwelling in that location.[58] [77] Pausanias has been told that the island is "covered with forests and total of animals, some wild, some tame. In this island there is also Achilles' temple and his statue".[78] Leuce had also a reputation every bit a identify of healing. Pausanias reports that the Delphic Pythia sent a lord of Croton to exist cured of a chest wound.[79] Ammianus Marcellinus attributes the healing to waters (aquae) on the island.[80]

A number of important commercial port cities of the Greek waters were dedicated to Achilles. Herodotus, Pliny the Elder and Strabo reported on the existence of a town Achílleion (Ἀχίλλειον), built by settlers from Mytilene in the sixth century BC, close to the hero'due south presumed burial mound in the Troad.[57] Later attestations point to an Achílleion in Messenia (according to Stephanus Byzantinus) and an Achílleios (Ἀχίλλειος) in Laconia.[81] Nicolae Densuşianu recognized a connection to Achilles in the names of Aquileia and of the northern arm of the Danube delta, called Chilia (presumably from an older Achileii), though his decision, that Leuce had sovereign rights over the Black Body of water, evokes modern rather than primitive sea-law.[75]

The kings of Epirus claimed to be descended from Achilles through his son, Neoptolemus. Alexander the Smashing, son of the Epirote princess Olympias, could therefore likewise merits this descent, and in many means strove to be like his great ancestor. He is said to have visited the tomb of Achilles at Achilleion while passing Troy.[82] In Advert 216 the Roman Emperor Caracalla, while on his way to state of war against Parthia, emulated Alexander by belongings games around Achilles' tumulus.[83]

Reception during antiquity

In Greek tragedy

The Greek tragedian Aeschylus wrote a trilogy of plays near Achilles, given the title Achilleis by modern scholars. The tragedies relate the deeds of Achilles during the Trojan War, including his defeat of Hector and eventual death when an arrow shot by Paris and guided by Apollo punctures his heel. Extant fragments of the Achilleis and other Aeschylean fragments take been assembled to produce a workable modern play. The kickoff office of the Achilleis trilogy, The Myrmidons, focused on the relationship betwixt Achilles and chorus, who represent the Achaean ground forces and attempt to convince Achilles to surrender his quarrel with Agamemnon; only a few lines survive today.[84] In Plato'south Symposium, Phaedrus points out that Aeschylus portrayed Achilles as the lover and Patroclus every bit the beloved; Phaedrus argues that this is incorrect because Achilles, being the younger and more than beautiful of the two, was the beloved, who loved his lover so much that he chose to die to avenge him.[85]

The tragedian Sophocles also wrote The Lovers of Achilles, a play with Achilles every bit the main grapheme. Only a few fragments survive.[86]

Towards the terminate of the 5th century BCE, a more than negative view of Achilles emerges in Greek drama; Euripides refers to Achilles in a bitter or ironic tone in Hecuba, Electra, and Iphigenia in Aulis.[87]

In Greek philosophy

Zeno

The philosopher Zeno of Elea centred one of his paradoxes on an imaginary footrace betwixt "swift-footed" Achilles and a tortoise, by which he attempted to show that Achilles could non grab upwardly to a tortoise with a caput start, and therefore that motility and change were impossible. Every bit a pupil of the monist Parmenides and a member of the Eleatic schoolhouse, Zeno believed time and motion to exist illusions.

Plato

In Hippias Minor, a dialogue attributed to Plato, an arrogant man named Hippias argues with Socrates. The two get into a discussion about lying. They decide that a person who is intentionally simulated must be "amend" than a person who is unintentionally faux, on the basis that someone who lies intentionally must understand the subject near which they are lying.[88] Socrates uses various analogies, discussing athletics and the sciences to testify his point. The two also reference Homer extensively. Socrates and Hippias concur that Odysseus, who concocted a number of lies throughout the Odyssey and other stories in the Trojan War Cycle, was faux intentionally. Achilles, like Odysseus, told numerous falsehoods. Hippias believes that Achilles was a generally honest human, while Socrates believes that Achilles lied for his own benefit. The 2 argue over whether it is meliorate to lie on purpose or by accident. Socrates somewhen abandons Homeric arguments and makes sports analogies to drive domicile the bespeak: someone who does incorrect on purpose is a better person than someone who does wrong unintentionally.

In Roman and medieval literature

The Romans, who traditionally traced their lineage to Troy, took a highly negative view of Achilles.[87] Virgil refers to Achilles equally a savage and a merciless butcher of men,[89] while Horace portrays Achilles ruthlessly slaying women and children.[90] Other writers, such as Catullus, Propertius, and Ovid, represent a second strand of disparagement, with an accent on Achilles' erotic career. This strand continues in Latin accounts of the Trojan State of war by writers such every bit Dictys Cretensis and Dares Phrygius and in Benoît de Sainte-Maure's Roman de Troie and Guido delle Colonne's Historia destructionis Troiae, which remained the most widely read and retold versions of the Matter of Troy until the 17th century.

Achilles was described past the Byzantine chronicler Leo the Deacon, non as Hellene, simply equally Scythian, while according to the Byzantine author John Malalas, his army was made up of a tribe previously known as Myrmidons and later as Bulgars.[91] [92]

In modern literature and arts

Achilles and Agamemnon by Gottlieb Schick (1801)

Literature

- Achilles appears in Dante'due south Inferno (equanimous 1308–1320). He is seen in Hell's 2d circle, that of lust.

- Achilles is portrayed equally a former hero who has get lazy and devoted to the love of Patroclus, in William Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida (1602).

- The French dramatist Thomas Corneille wrote a tragedy La Mort d'Achille (1673).

- Achilles is the field of study of the verse form Achilleis (1799), a fragment past Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

- In 1899, the Polish playwright, painter and poet Stanisław Wyspiański published a national drama, based on Polish history, named Achilles.

- In 1921, Edward Shanks published The Isle of Youth and Other Poems, concerned among others with Achilles.

- The 1983 novel Kassandra by Christa Wolf as well treats the death of Achilles.

- Akhilles is killed past a poisoned Kentaur arrow shot past Kassandra in Marion Zimmer Bradley's novel The Firebrand (1987).

- Achilles is one of diverse 'narrators' in Colleen McCullough'southward novel The Vocal of Troy (1998).

- The Death of Achilles (Смерть Ахиллеса, 1998) is an historical detective novel by Russian writer Boris Akunin that alludes to diverse figures and motifs from the Iliad.

- The character Achilles in Ender'south Shadow (1999), by Orson Scott Menu, shares his namesake's cunning mind and ruthless attitude.

- Achilles is one of the main characters in Dan Simmons's novels Ilium (2003) and Olympos (2005).

- Achilles is a major supporting character in David Gemmell's Troy series of books (2005–2007).

- Achilles is the main graphic symbol in David Malouf'south novel Ransom (2009).

- The ghost of Achilles appears in Rick Riordan's The Last Olympian (2009). He warns Percy Jackson almost the Curse of Achilles and its side effects.

- Achilles is a principal character in Terence Hawkins' 2009 novel The Rage of Achilles.

- Achilles is a major character in Madeline Miller's debut novel, The Vocal of Achilles (2011), which won the 2012 Orangish Prize for Fiction. The novel explores the relationship betwixt Patroclus and Achilles from boyhood to the fateful events of the Iliad.

- Achilles appears in the light novel series Fate/Apocrypha (2012–2014) as the Passenger of Ruby.

- Achilles is a main character in Pat Barker's 2018 novel The Silence of the Girls, much of which is narrated by his slave Briseis.

Visual arts

- Achilles with the Daughters of Lycomedes is a subject treated in paintings past Anthony van Dyck (before 1618; Museo del Prado, Madrid) and Nicolas Poussin (c. 1652; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) among others.

- Peter Paul Rubens has authored a series of works on the life of Achilles, comprising the titles: Thetis dipping the infant Achilles into the river Styx, Achilles educated by the centaur Chiron, Achilles recognized among the daughters of Lycomedes, The wrath of Achilles, The death of Hector, Thetis receiving the arms of Achilles from Vulcanus, The decease of Achilles (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam), and Briseis restored to Achilles (Detroit Establish of Arts; all c. 1630–1635)

- Pieter van Lint, "Achilles Discovered amid the Daughters of Lycomedes", 1645, at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

- Dying Achilles is a sculpture created past Christophe Veyrier (c. 1683; Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

- The Rage of Achilles is a fresco by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1757, Villa Valmarana Ai Nani, Vicenza).

- Eugène Delacroix painted a version of The Education of Achilles for the ceiling of the Paris Palais Bourbon (1833–1847), one of the seats of the French Parliament.

- Arthur Kaan [de] created a statue group Achilles and Penthesilea (1895; Vienna).

- Achilleus (1908) is a lithography past Max Slevogt.

Music

Achilles has been frequently the subject of operas, ballets and related genres.

- Operas titled Deidamia were composed by Francesco Cavalli (1644) and George Frideric Handel (1739).

- Achille et Polyxène (Paris 1687) is an opera begun by Jean-Baptiste Lully and finished by Pascal Collasse.

- Achille et Déidamie (Paris 1735) is an opera composed by André Campra.

- Achilles (London 1733) is a ballad opera, written by John Gay, parodied past Thomas Arne every bit Achilles in petticoats in 1773.

- Achille in Sciro is a libretto by Metastasio, equanimous by Domenico Sarro for the inauguration of the Teatro di San Carlo (Naples, 4 November 1737). An even earlier limerick is from Antonio Caldara (Vienna 1736). Afterwards operas on the same libretto were composed past Leonardo Leo (Turin 1739), Niccolò Jommelli (Vienna 1749 and Rome 1772), Giuseppe Sarti (Copenhagen 1759 and Florence 1779), Johann Adolph Hasse (Naples 1759), Giovanni Paisiello (Saint petersburg 1772), Giuseppe Gazzaniga (Palermo 1781) and many others. It has also been ready to music every bit Il Trionfo della gloria.

- Achille (Vienna 1801) is an opera by Ferdinando Paër on a libretto past Giovanni de Gamerra.

- Achille à Scyros (Paris 1804) is a ballet by Pierre Gardel, composed past Luigi Cherubini.

- Achilles, oder Das zerstörte Troja ("Achilles, or Troy Destroyed", Bonn 1885) is an oratorio by the High german composer Max Bruch.

- Achilles auf Skyros (Stuttgart 1926) is a ballet by the Austrian-British composer and musicologist Egon Wellesz.

- Achilles' Wrath is a concert piece by Sean O'Loughlin.[93]

- Achilles Final Stand a rail on the 1976 Led Zeppelin album Presence.

- Achilles, Agony and Ecstasy in Eight Parts is the first song on the 1992 Manowar album The Triumph of Steel.

- Achilles Come up Down is a song on the 2017 Gang of Youths album Become Farther in Lightness.

Film and television

In films Achilles has been portrayed in the post-obit films and television series:

- The 1924 picture show Helena by Carlo Aldini

- The 1954 moving picture Ulysses by Piero Lulli

- The 1956 film Helen of Troy by Stanley Baker

- The 1961 moving picture The Trojan Horse by Arturo Dominici

- The 1962 film The Fury of Achilles by Gordon Mitchell

- The 1997 goggle box miniseries The Odyssey by Richard Trewett

- The 2003 television receiver miniseries Helen of Troy by Joe Montana

- The 2004 film Troy by Brad Pitt

- The 2018 TV series Troy: Fall of a Urban center by David Gyasi

Architecture

- In 1890, Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria, had a summer palace built in Corfu. The edifice is named the Achilleion, later Achilles. Its paintings and statuary describe scenes from the Trojan War, with detail focus on Achilles.

- The Wellington Monument is a statue representing Achilles erected as a memorial to Arthur Wellesley, the start knuckles of Wellington, and his victories in the Peninsular War and the latter stages of the Napoleonic Wars.

Namesakes

- The name of Achilles has been used for at least ix Majestic Navy warships since 1744 – both as HMSAchilles and with the French spelling HMSAchille. A sixty-gun ship of that proper noun served at the Battle of Belleisle in 1761 while a 74-gun ship served at the Battle of Trafalgar. Other boxing honours include Walcheren 1809. An armored cruiser of that proper name served in the Royal Navy during the Start World War.

- HMNZSAchilles was a Leander-class cruiser which served with the Royal New Zealand Navy in World State of war II. It became famous for its function in the Boxing of the River Plate, alongside HMSAjax and HMSExeter. In improver to earning the battle honour 'River Plate', HMNZS Achilles likewise served at Guadalcanal 1942–1943 and Okinawa in 1945. After returning to the Royal Navy, the ship was sold to the Indian Navy in 1948, but when she was scrapped parts of the ship were saved and preserved in New Zealand.

- A species of lizard, Anolis achilles, which has widened heel plates, is named for Achilles.[94]

Gallery

-

Achilles sacrificing to Zeus for Patroclus' safe return,[95] from the Ambrosian Iliad, a 5th-century illuminated manuscript

-

Achilles and Penthesilea fighting, Lucanian blood-red-figure bell-krater, late 5th century BC

-

Achilles killing Penthesilea, tondo of an Attic cerise-figure kylix, c. 465 BC, from Vulci.

-

Thetis and the Nereids mourning Achilles, Corinthian blackness-effigy hydria, c. 555 BC (Louvre, Paris)

-

Caput of Achilles depicted on a 4th-century BC money from Kremaste, Phthia. Reverse: Thetis, wearing and belongings the shield of Achilles with his AX monogram.

-

Achilles on a Roman mosaic with the Removal of Briseis, 2nd century

References

- ^ a b c d Dorothea Sigel; Anne Ley; Bruno Bleckmann. "Achilles". In Hubert Cancik; et al. (eds.). Achilles. Brill'south New Pauly. Brill Reference Online. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e102220. Accessed v May 2017.

- ^ a b Robert South. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, pp. 183ff.

- ^ Epigraphical database gives 476 matches for Ἀχιλ-.The earliest ones: Corinth 7th c. BC, Delphi 530 BC, Attica and Elis 5th c. BC.

- ^ Scholia to the Iliad, one.1.

- ^ Leonard Palmer (1963). The Interpretation of Mycenaean Greek Texts. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 79.

- ^ a b Gregory Nagy. "The best of the Achaeans". CHS. The Eye for Hellenic Studies, Harvard University. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Cf. the Wiktionary entries "Ἀχιλλεύς" and *h₂eḱ-.

- ^ Iliad 1.121, 2.688.

- ^ E. g. Iliad 1.58, one.84, one.148, one.215, i.364, 1.489.

- ^ Cf. the supportive position of Hildebrecht Hommel (1980). "Der Gott Achilleus". Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften (1): 38–44. – A critical signal of view is taken by J. T. Hooker (1988). "The cults of Achilleus". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 131 (iii): i–7.

- ^ Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 755–768; Pindar, Nemean 5.34–37, Isthmian viii.26–47; Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.13.5; Poeticon astronomicon 2.15.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.13.5.

- ^ Statius, Achilleid 1.269; Hyginus, Fabulae 107.

- ^ Jonathan Southward. Burgess (2009). The Death and Afterlife of Achilles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Printing. p. 9. ISBN978-0-8018-9029-one . Retrieved five February 2010.

- ^ Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4.869–879.

- ^ Homer (Robert Fagles translation). The Iliad. p. 525.

Simply the other (spear) grazed Achilles' strong right arm and nighttime claret gushed as the spear shot past his back

- ^ Hesiod, Catalogue of Women, fr. 204.87–89 MW; Iliad 11.830–832.

- ^ Iliad 9.410ff.

- ^ Photius, Bibliotheca, cod. 190: "Thetis burned in a undercover place the children she had by Peleus; vi were born; when she had Achilles, Peleus noticed and tore him from the flames with just a burnt foot and confided him to Chiron. The latter exhumed the body of the behemothic Damysos who was cached at Pallene—Damysos was the fastest of all the giants—removed the 'astragale' and incorporated it into Achilles' pes using 'ingredients'. This 'astragale' brutal when Achilles was pursued by Apollo and information technology was thus that Achilles, fallen, was killed. It is said, on the other hand, that he was called Podarkes by the Poet, because, it is said, Thetis gave the newborn child the wings of Arce and Podarkes ways that his feet had the wings of Arce."

- ^

1 or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain : Murray, John (1833). A Classical Manual: Existence a Mythological, Historical and Geographical Commentary on Pope's Homer, and Dryden'due south Aeneid of Virgil, with a Copious Index. Albemarle Street, London. p. 3.

1 or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain : Murray, John (1833). A Classical Manual: Existence a Mythological, Historical and Geographical Commentary on Pope's Homer, and Dryden'due south Aeneid of Virgil, with a Copious Index. Albemarle Street, London. p. 3. - ^ Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Book half-dozen (summary from Photius, Myriobiblon 190) (trans. Pearse) (Greek mythographer C1st to C2nd A.D.) : "It is said . . . that he [Akhilleus (Achilles)] was called Podarkes (Podarces, Swift-Footed) by the Poet [i.e. Homer], considering, information technology is said, Thetis gave the newborn kid the wings of Arke (Arce) and Podarkes means that his anxiety had the wings of Arke. And Arke was the daughter of Thaumas and her sister was Iris; both had wings, but, during the struggle of the gods against the Titanes (Titans), Arke flew out of the camp of the gods and joined the Titanes. Later the victory Zeus removed her wings earlier throwing her into Tartaros and, when he came to the hymeneals of Peleus and Thetis, he brought these wings as a gift for Thetis.

- ^ Euripides, Skyrioi, surviving only in fragmentary form; Philostratus Inferior, Imagines i; Scholiast on Homer's Iliad, 9.326; Ovid, Metamorphoses xiii.162–180; Ovid, Tristia 2.409–412 (mentioning a Roman tragedy on this subject); Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.13.8; Statius, Achilleid ane.689–880, ii.167ff.

- ^ Graves, Robert (2017). The Greek Myths - The Complete and Definitive Edition. Penguin Books Express. pp. Index s.v. Aissa. ISBN9780241983386.

- ^ Graves, Robert (2017). The Greek Myths - The Complete and Definitive Edition. Penguin Books Limited. p. 642. ISBN9780241983386.

- ^ Iliad 16.168–197.

- ^ a b Pseudo-Apollodorus. "Bibliotheca, Epitome three.20". theoi.com.

- ^ "Proclus' Summary of the Cypria". Stoa.org. Archived from the original on 9 Oct 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ "Dares' account of the devastation of Troy, Greek Mythology Link". Homepage.mac.com. Archived from the original on xxx November 2001. Retrieved ix March 2010.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.151.

- ^ Iliad 24.257. Cf. Vergil, Aeneid one.474–478.

- ^ a b " Troilus: GreekMythology.com accessed xxx September 2019

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca Prototype three.32.

- ^ Scholia to Lycophron 307; Servius, Scholia to the Aeneid i.474.

- ^ James Davidson, "Zeus Be Nice Now" in London Review of Books, nineteen July 2007. Accessed 23 October 2007.

- ^ Plautus, Bacchides 953ff.

- ^ Iliad 9.334–343.

- ^ "The Iliad", Fagles translation. Penguin Books, 1991: 22.346.

- ^ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Illiad of Homer . Chicago: The University of Chicago. ISBN978-0-226-46937-9.

- ^ Propertius, iii.11.15; Quintus Smyrnaeus one.

- ^ Robin Play a joke on (2011). The Tribal Imagination: Civilization and the Savage Mind. Harvard University Press. p. 223. ISBN9780674060944.

There is certainly no evidence in the text of the Iliad that Achilles and Patroclus were lovers.

- ^ Martin, Thomas R (2012). Alexander the Great: The Story of an Ancient Life. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN978-0521148443.

The ancient sources practise not report, withal, what modern scholars accept asserted: that Alexander and his very shut friend Hephaestion were lovers. Achilles and his as shut friend Patroclus provided the legendary model for this friendship, simply Homer in the Iliad never suggested that they had sexual practice with each other. (That came from after authors.)

- ^ Plato, Symposium, 180a; the beauty of Achilles was a topic already broached at Iliad ii.673–674.

- ^ Kenneth Dover, Greek Homosexuality (Harvard University Press, 1978, 1989), p. 1 et passim.

- ^ Abrantes 2016: c. four.3.i

- ^ Odyssey 24.36–94.

- ^ Richmond Lattimore (2007). The Odyssey of Homer. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 347. ISBN978-0-06-124418-half dozen.

- ^ E. Hamilton (1969), Mythology. New York: Penguin Books.

- ^ Odyssey eleven.467–564.

- ^ "Alexander came to rest at Phaselis, a coastal city which was later renowned for the possession of Achilles' original spear." Robin Lane Fox, Alexander the Peachy, 1973, p. 144.

- ^ Pausanias, iii.3.6; run across Christian Jacob and Anne Mullen-Hohl, "The Greek Traveler's Areas of Knowledge: Myths and Other Discourses in Pausanias' Description of Greece", Yale French Studies 59: Rethinking History: Fourth dimension, Myth, and Writing (1980:65–85, especially 81).

- ^ "Petteia". Archived 9 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Greek Lath Games". Archived 8 Apr 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Latrunculi". Archived fifteen September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ioannis Kakridis (1988). Ελληνική Μυθολογία [Greek mythology]. Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. Vol. 5, p. 92.

- ^ a b Rose, Charles Brian (2014). The Archaeology of Greek and Roman Troy. Cambridge Academy Printing. p. 79. ISBN9780521762076.

- ^ Cf. Homer, Iliad 24.lxxx–84.

- ^ a b Herodotus, Histories five.94; Pliny, Naturalis Historia five.125; Strabo, Geographica 13.ane.32 (C596); Diogenes Laërtius 1.74.

- ^ a b c d e f Guy Hedreen (July 1991). "The Cult of Achilles in the Euxine". Hesperia. 60 (three): 313–330. doi:x.2307/148068. JSTOR 148068.

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.45.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Hellenic republic iii.20.8.

- ^ Lycophron 856.

- ^ Burgess, Jonathan Due south. (2009). The Decease and Afterlife of Achilles. JHU Press. p. 114. ISBN9781421403618.

- ^ Burgess, Jonathan Southward. (2009). The Death and Afterlife of Achilles. JHU Press. p. 116. ISBN9781421403618.

- ^ Perseus Under Philologic: Str. 13.one.32.

- ^ Hildebrecht Hommel (1980). "Der Gott Achilleus". Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften (1): 38–44.

- ^ J. T. Hooker (1988). "The cults of Achilleus". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 131 (3): 1–7.

- ^ Quintus Smyrnaeus, three.770–779.

- ^ Pliny, Naturalis Historia 4.12.83 (chapter 4.26).

- ^ Pliny, Naturalis Historia 4.13.93 (chapter 4.27): "Researches which accept been made at the nowadays 24-hour interval place this island at a distance of 140 miles from the Borysthenes, of 120 from Tyras, and of fifty from the island of Peuce. It is about ten miles in circumference." Though afterwards he speaks again of "the remaining islands in the Gulf of Carcinites" which are "Cephalonesos, Rhosphodusa [or Spodusa], and Macra".

- ^ Pomponius Mela, De situ orbis two.7.

- ^ Proclus, Chrestomathia two.

- ^ Pindar, Nemea 4.49ff.; Arrian, Periplus of the Euxine Ocean 21.

- ^ Pindar, Olympia 2.78ff.

- ^ D. Page, Lyrica Graeca Selecta, Oxford 1968, p. 89, no. 166.

- ^ a b Nicolae Densuşianu: Dacia preistorică. Bucharest: Ballad Göbl, 1913.

- ^ Dionysius Periegetes, Orbis descriptio 5.541, quoted in Densuşianu 1913.

- ^ Arrian, Periplus of the Euxine Sea 21; Scholion to Pindar, Nemea 4.79.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Hellenic republic 3.xix.11.

- ^ Pausanias, Clarification of Greece iii.19.13.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae 22.8.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Hellenic republic 3.25.4.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri ane.12.1, Cicero, Pro Archia Poeta 24.

- ^ Dio Cassius 78.sixteen.7.

- ^ Pantelis Michelakis, Achilles in Greek Tragedy, 2002, p. 22

- ^ Plato, Symposium, translated Benjamin Jowett, Dover Thrift Editions, page 8

- ^ S. Radt. Tragicorum Graecorum fragmenta, vol. four, (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1977) frr. 149–157a.

- ^ a b Latacz 2010

- ^ Jowett, Benjamin; Plato (xv January 2013). "Lesser Hippias". Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Aeneid 2.28, 1.thirty, 3.87.

- ^ Odes 4.6.17–twenty.

- ^ Ekonomou, Andrew (2007). Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes. Britain: Lexington Books. p. 123. ISBN9780739119778 . Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Jeffreys, Elizabeth; Croke, Brian (1990). Studies in John Malalas. Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, Section of Modern Greek, University of Sydney. p. 206. ISBN9780959362657 . Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Entry at Musical World.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Academy Press. thirteen + 296 pp. ISBN 978-i-4214-0135-five. ("Achilles", p. 1).

- ^ Iliad sixteen.220–252.

Further reading

- Ileana Chirassi Colombo (1977), "Heroes Achilleus – Theos Apollon." In Il Mito Greco, edd. Bruno Gentili and Giuseppe Paione. Rome: Edizione dell'Ateneo e Bizzarri.

- Anthony Edwards (1985a), "Achilles in the Underworld: Iliad, Odyssey, and Æthiopis". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 26: pp. 215–227.

- Anthony Edwards (1985b), "Achilles in the Odyssey: Ideologies of Heroism in the Homeric Ballsy". Beiträge zur klassischen Philologie. 171.

- Edwards, Anthony T. (1988). "ΚΛΕΟΣ ΑΦΘΙΤΟΝ and Oral Theory". The Classical Quarterly. 38: 25–30. doi:10.1017/S0009838800031220.

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths, Harmondsworth, London, England, Penguin Books, 1960. ISBN 978-0143106715

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths: The Complete and Definitive Edition. Penguin Books Limited. 2017. ISBN 978-0-241-98338-6, 024198338X

- Guy Hedreen (1991). "The Cult of Achilles in the Euxine". Hesperia. American School of Classical Studies at Athens. sixty (3): 313–330. doi:10.2307/148068. JSTOR 148068.

- Karl Kerényi (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. New York/London: Thames and Hudson.

- Jakob Escher-Bürkli: Achilleus ane. In: Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (RE). Vol. I,ane, Stuttgart 1893, Col. 221–245.

- Joachim Latacz (2010). "Achilles". In Anthony Grafton; Glenn Most; Salvatore Settis (eds.). The Classical Tradition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Academy Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN978-0-674-03572-0.

- Hélène Monsacré (1984), Les larmes d'Achille. Le héros, la femme et la souffrance dans la poésie d'Homère, Paris: Albin Michel.

- Gregory Nagy (1984), The Name of Achilles: Questions of Etymology and 'Folk Etymology, Illinois Classical Studies. 19.

- Gregory Nagy (1999), The All-time of The Acheans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Johns Hopkins University Press (revised edition, online).

- Dorothea Sigel; Anne Ley; Bruno Bleckmann. "Achilles". In Hubert Cancik; et al. (eds.). Achilles. Brill's New Pauly. Brill Reference Online. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e102220.

- Dale Southward. Sinos (1991), The Entry of Achilles into Greek Epic, PhD thesis, Johns Hopkins University. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms International.

- Jonathan S. Burgess (2009), The Death and Afterlife of Achilles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Abrantes, M.C. (2016), Themes of the Trojan Cycle: Contribution to the written report of the greek mythological tradition (Coimbra). ISBN 978-1530337118

External links

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Achilles. |

| | Await up Achillean in Wiktionary, the costless dictionary. |

- Trojan State of war Resource

- Gallery of the Ancient Art: Achilles

- – via Wikisource. Verse form by Florence Earle Coates

whittleseliestionce.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achilles

0 Response to "for what is achilles willing to fight and for what does he refuse to fight?"

Postar um comentário